Ever since I added pthreads to Ag, major performance improvements have been hard to come by. I continue to experiment with optimizations, but the low-hanging fruit has been picked.

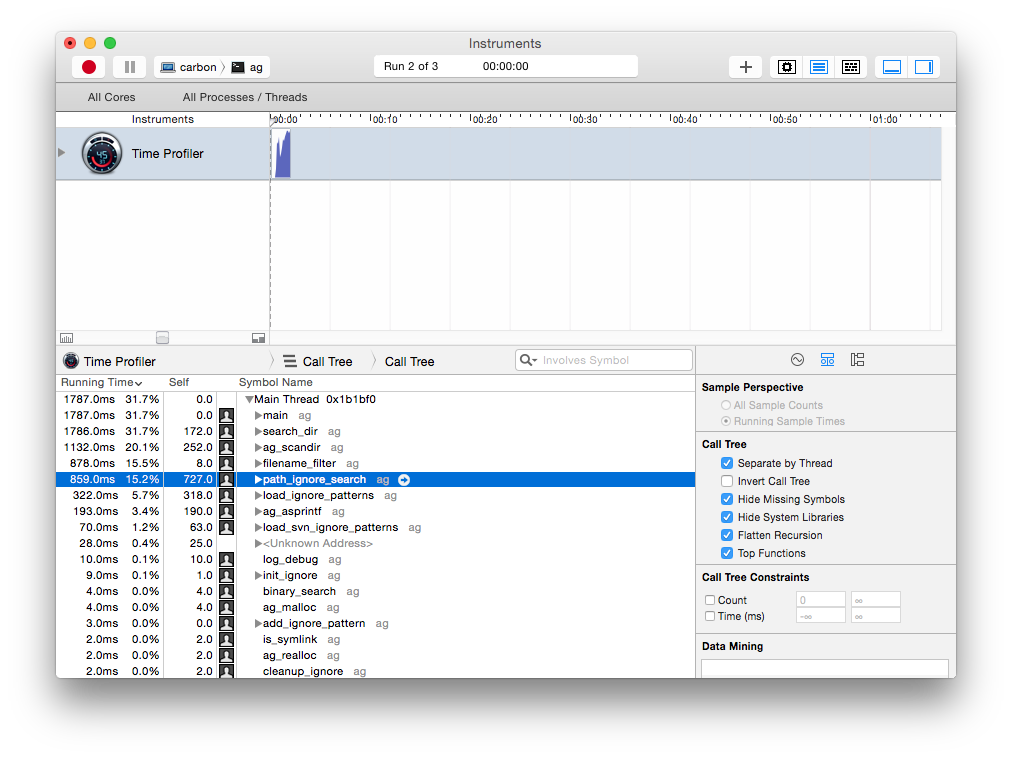

My approach to optimization is rather straightforward: I profile with real-world data, then think of ways to make the time-consuming functions faster. Below is a profile from searching ~/code/ on my laptop. The directory is 6.7GB, though Ag only searches 0.76GB of that. Filesystem cache is hot.

Some readers may not be intimately familiar with Ag’s internals, so I’ll spell-out what this profile tells me. Basically, Ag is spending most of its time doing two things:

-

Figuring out which files to search.

-

Searching those files for matches.

Time spent in other bits is negligible, meaning those parts aren’t worth optimizing. For example: if through some valiant effort I made debug logging 20x faster, it would only improve this run by 10 milliseconds. Amdahl’s Law laughs in the face of micro-optimizations.

Alas, there’s not much more I can do about #2, searching through files. I already use tricks like Boyer-Moore strstr, mmap()ed I/O, and PCRE-JIT. That leaves optimizing #1, figuring out which files to search. In the screenshot above, Ag spent 727 milliseconds in path_ignore_search(). This single function accounted for 15% of total execution time. Worse, it’s in the main thread. Worker threads could be sitting idle, waiting for the main thread to supply them with paths to search. Improving this function could have knock-on effects.

The poor performance of path_ignore_search() is understantable. Its job is to figure out if a file should be ignored or not. That means consulting patterns in .gitignore, .hgignore, .ignore, etc. In addition, it must check for matching patterns in the file’s parent directores. Is ~/code/ag/tests/one_device.t.err ignored? The answer can depend on .*ignore files in ~/code/ag/tests/, ~/code/ag/, ~/code/, and even the user’s global ignore patterns. Ag must do all of this for every file it comes across. To get some idea of the complexity and magnitude of these operations, try searching with --debug. Most of Ag’s output will be related to ignores.

Correctly ignoring files is difficult; doing it efficiently is even trickier. If *.tar is in ~/.gitignore, Ag must run fnmatch("*.tar", ...) on every file it encounters. The number of calls to fnmatch() are doubled with two regexes in the root ignore, tripled for three, and so on. Algorithmically speaking, this is O(n * m), where n is the number of ignore patterns and m is the number of files. With so many patterns and files, it’s amazing Ag is fast at all.

I’ve known about this bottleneck for a while, and tried to ameliorate it with some basic optimizations. Patterns without regex characters (*, !, ?, etc) are stored in sorted arrays. These can be binary searched, giving O(log(n) * m) performance. Unfortunately, many patterns are regexes. For those, there’s simply no way to avoid the inefficient calls to fnmatch().

Until a few weeks ago, that’s where I was stuck. When it came to making regex patterns faster, I had no promising ideas. Then I realized: many regex patterns are for file extensions. Typically, people just want to ignore *.gz or *.zip. If I special-cased these patterns, I could reduce calls to fnmatch(). Even better, I could reuse a trick and store them in sorted arrays for efficient searching.

Behold. There are a few other minor tweaks in that pull request, but I went back and made a version of Ag without extension optimizations so that this post’s benchmarks and profiling data wouldn’t be misleading. There’s also a dumb bug on line 381 of ignore.c, but I’ve since fixed it.

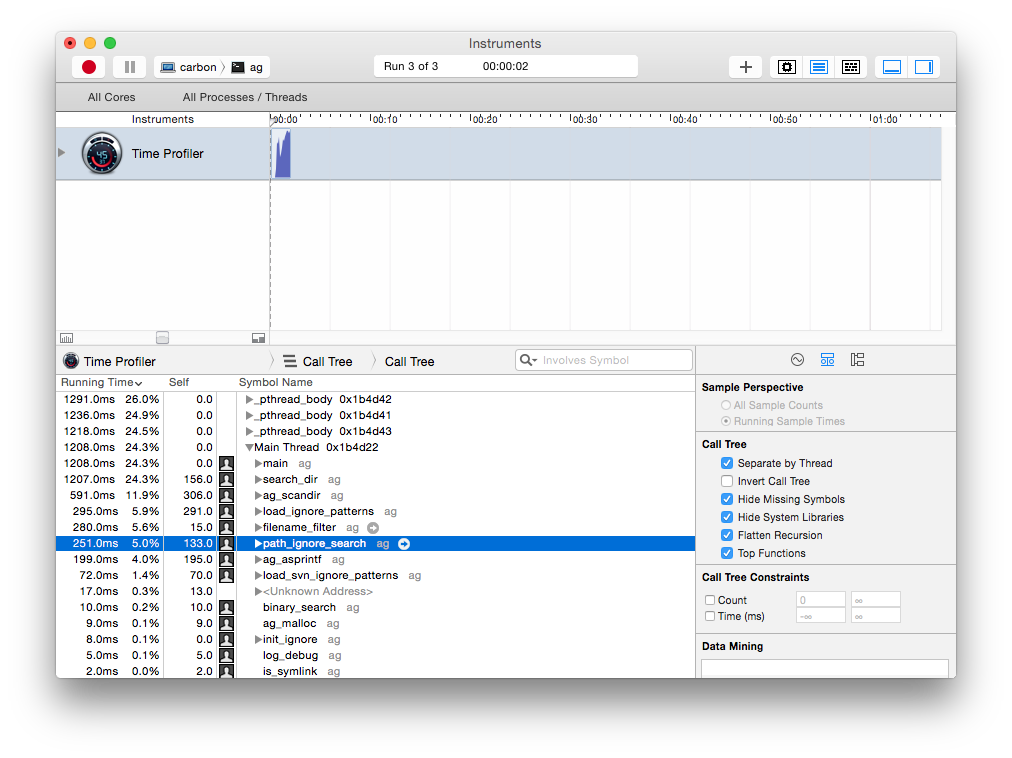

Searching the same data as before, profiling confirms the speedup in path_ignore_search():

133 milliseconds, over 5x faster! Impressive, but how much does it improve overall performance? Here’s a run of the unoptimized version on my laptop. Again, my ~/code/ directory is 6.7GB and Ag searches 0.76GB of it.

ggreer@carbon:~/code% time ./ag/ag cpu_set_t

...

./ag/ag cpu_set_t 2.93s user 2.31s system 281% cpu 1.859 total1.86 seconds. Now with extension-detection:

ggreer@carbon:~/code% time ./ag/ag cpu_set_t

...

./ag/ag cpu_set_t 2.38s user 2.22s system 310% cpu 1.483 total1.48 seconds. A 25% improvement. Not bad.[1] The guess about knock-on effects was correct.

Overall, I’m pleased with this optimization. It doesn’t add much complexity, but it improves performance significantly. If you’re ever in a similar situation (stumped trying to optimize some code), remember that you don’t have to speedup every possible input with a single algorithm. Sometimes, the only thing you can do is handle a plurality of inputs with a special case algorithm. It’s not as good as the ideal, but it’s better than nothing.

Thanks to Bjorn Tipling for proofreading this post.

- In case you doubt my methodology: I’m not cherry-picking these results. They’re medians of 5 runs. Variance was < 0.05 seconds.